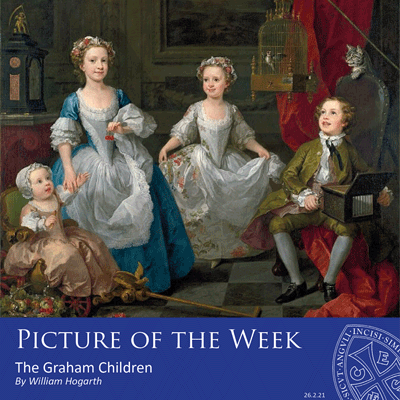

We are living through extraordinary times, it is true, and children are undoubtedly hindered by lockdowns but seeing what wealthy children from other centuries had to contend with gives pause for thought.

Sarah Carr Gomm, Head of History of Art

William Hogarth, The Graham Children, 1742, 160 x 181 cm, oil on canvas, National Gallery London

The Graham children were the two sons and two daughters of Daniel Graham, apothecary to King George I and II and The Chelsea Hospital. Known as a ‘conversation piece’ for its informality, the painting shows the figures in their fine clothes and in their more than comfortable home.

To the left of centre, in blue, Henrietta stands upright in the place of a mother, holding her baby brother’s hand and she looks to the spectator for assurance. Next to her, her sister, Anna Maria, takes a dainty step and the serpentine curve made by the white frills of their low-cut dresses, hems and bonnets plays across the composition and unites them. She holds her skirts up and points her foot as if about to dance, her attention caught by the music of the serinette, or bird organ, that her brother Richard is playing. He is not interested in any of his siblings but is encouraging the finch in the gilded cage to sing, but its chirping is probably due to the greedy tabby cat that has climbed up the back of his chair and is ready to pounce if given the chance. On the music box you can just about make out the image of Orpheus with his lyre, who charmed the animals with his music, but the idyll didn’t last.

On the left is baby Thomas who is wearing a dress as boys as well as girls used to do until they were ‘breeched’, that is until they were potty trained and could cope with the buttons when desperate. He was born in 1740 and died as Hogarth was at work on this painting. Throughout, there are references to the fragility of life, not least in childhood when infant mortality ran high: Thomas sits in a cart where the wooden bird’s outstretched wings representing the flight of his tiny soul; below him is a gorgeously painted silver bowl with cascading fruit which ripens and quickly withers; a carnation lying beside the bowl is a symbol of remembrance; above him on a clock is a small winged figure with a scythe and hour glass and, next to him, his sister is holding out cherries, the ‘fruit of paradise’, which he stretches up to grasp.

Hogarth’s marriage was childless and he had a profound empathy for children of all walks of life. He was a great friend of Thomas Coram whose institution for abandoned children he helped found and he and his wife fostered several. Although the Graham children are imitating adults and behaving properly for their proud parents, Hogarth shows that they can be young too; they are wrapped up in their own thoughts, unaware of each other, and only the eldest knows that there is world outside the safety of their home. He not only paints their portraits, but he also gives us a warning of the vulnerability of childhood and of the swift passage of time.

Carpe diem!