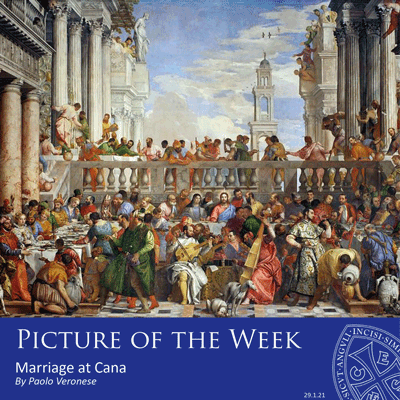

Father Kenny tells me that the Gospel reading last Sunday, in this ongoing season of Epiphanytide, was the story of Christ’s miracle at the Marriage at Cana and in order to see the most sumptuous of all depictions of the subject, we have to leave the National Gallery and go to the Louvre.

Sarah Carr Gomm, Head of History of Art

Paolo Veronese, Marriage at Cana, 1562-63, 660 x 990 cm, Louvre, Paris

On this massive canvas, Veronese displays the most lavish of weddings. The guests sit at a u-shaped table against a stage-set of the latest sixteenth-century architecture and are dressed in their finest and most colourful clothes. Christ, with a halo and in place of honour at the centre of the composition, next to Mary His Mother and some disciples, takes a minute to spot as he sits passively, not drawing our attention away from joyous occasion, though the miracle of turning water into wine is evident in the number of ewers being filled and glasses raised. The bride and groom are harder to find: they sit as guests at the far left of the painting, not looking particularly happy or amazed by the miracle; the figures on their left look fixated by her jewelry; a couple gossip; an eastern-looking figure ruminates; a woman in blue is picking her teeth, and in front of them all is a steward in green and a dwarf with a pet parrot. Another such indulgent feast scene, this time of the Last Supper, got Veronese into trouble with the Inquisition as they suspected him of heresy, and we have the transcript of the trial. When asked why he included such details, he replied that he had to fill the canvas with something and, with one this size, he does have a point.

To make the wedding go with a swing, Veronese has placed a band in the centre of the foreground and he has included himself, in white, playing the viola da braccio. The musicians accompanying him are portraits of the other great Venetian painters of his age: Jacopo Bassano on the cornetto; Tintoretto also playing a viola da braccio; and Titian, in red, playing the violone. Although they add a festive note to the banquet, there is an hourglass on the table between them to remind us that life is short.

The Marriage at Cana was commissioned by the Benedictine monks of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice for their refectory. Veronese cleverly designed the architecture in the painting to fit with the real details in the room, thereby making it an illusionistic extension of the space where it hung. Perhaps the artist intended this scene, the first of Christ’s miracles by which he reveals his divine status, to be a representation of the vanities and transience of this world – but it’s hard to think of the poor monks looking at it while they ate their gruel.

With this Wikimedia link you can really see the details.