‘Tyger, Tyger, burning bright, / In the forests of the night; / What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?’ – William Blake

What is it about tigers? Friday’s ‘Pic of the Week’ – Rousseau’s fabulous Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!) – got me thinking about tigers in poetry. William Blake’s The Tyger may well be familiar to you. Like Rousseau, Blake never saw an actual tiger (as his illustration shows); still, for him the tiger represented the most terrifying of God’s creations: ‘Did he who made the lamb, make thee?’

Then T.S. Eliot, in his poem, Gerontion, has his speaker – a dying old man – terrified of ‘Christ the tiger’: for him, the gentle lamb of God has become the tiger of fierce judgment. Echoing Blake, Elizabeth Jennings, in her poem In Praise of Creation (studied by our Year 11s), sees in ‘the one flash of the tiger’s eye’ evidence of divine design; for Jennings, as for Blake and Eliot, the tiger represents the ultimate predator: awesome, irresistible, terrifying.

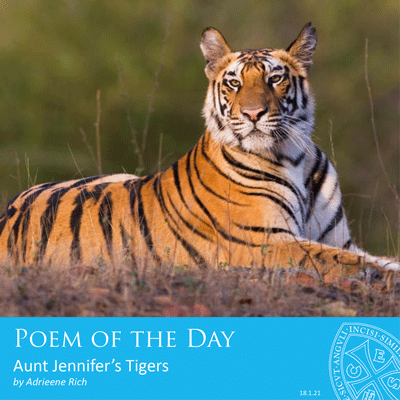

And so to today’s poem, Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers by the American poet, Adrienne Rich. These tigers – embroidered by the speaker’s elderly aunt – are not so much terrifying as flamboyant, almost camp: they ‘prance’ and ‘pace in sleek, chivalric certainty’. They are no more realistic than Rousseau’s tiger, the creations not of God but of an artist, in this case Aunt Jennifer. What can they mean? What, if anything, has their fearless disregard for ‘the men beneath the tree’ to do with the aunt? Why does Rich describe the (unnamed) Uncle’s wedding ring as ‘a massive weight’, which ‘sits heavily on Aunt Jennifer’s hand’?

Anticipating the aunt’s death, Rich contrasts her ‘terrified’ hands, ‘mastered’ by (unspecified) ‘ordeals’, with the vitality of her surviving artwork: ‘The tigers in the panel that she made / Will go on prancing, proud and unafraid.’ The poem was written in the 1950s, when American Second Wave feminists were challenging afresh the repressive institutions of their highly conservative society, including that of marriage. Does this social context help us to interpret the symbolism of these tigers? Or should we just delight in the image (and sound) of them, ‘prancing, proud and unafraid’? In the style of Mr Fernandes – and indeed the poem – I’ll leave you to answer such questions for yourselves!

Andrew Macdonald-Brown

Teacher of English and Classics

Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers

by Adrienne Rich

Aunt Jennifer’s tigers prance across a screen,

Bright topaz denizens of a world of green.

They do not fear the men beneath the tree;

They pace in sleek chivalric certainty.

Aunt Jennifer’s finger fluttering through her wool

Find even the ivory needle hard to pull.

The massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band

Sits heavily upon Aunt Jennifer’s hand.

When Aunt is dead, her terrified hands will lie

Still ringed with ordeals she was mastered by.

The tigers in the panel that she made

Will go on prancing, proud and unafraid.