Here we go again! I am sure some of us are feeling somewhat dispirited and there will have been many disappointments – get-togethers postponed, outings abandoned and trips abroad cancelled. My Upper Sixth Form students and I have been looking at a painting which took us far afield and it is always good to do a bit of armchair travelling particularly when we cannot take off for real.

Sarah Carr Gomm, Head of History of Art

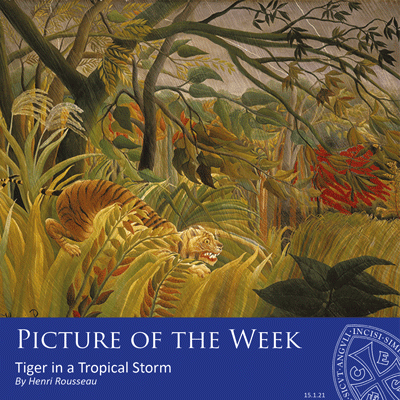

Henri Rousseau, (1844-1910), Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!), 1891, oil on canvas, 130 x 162 cm, National Gallery London.

The painting depicts a tiger in a forest in the midst of a tropical downpour. The rain lashes across the canvas and a flash of lightening in the dark sky illuminates the thickly woven leaves, the branches swaying in the wind and the wide-eyed tiger, crouching down, which is about to pounce on its prey. Its victim is to the right of the frame, beyond our view, and we are left to guess the outcome (although Rousseau later said that the tiger was about to attack a group of explorers!).

Rousseau’s distinctive style is known as ‘naïve’ or ‘primitive’ because, as he had no formal training, his art does not follow academic conventions. He had a spell in the army and claimed that during his military service he was sent to Mexico where he saw wild beasts in the jungle. There is, however, no evidence to suggest that he ever left France. Instead, he found inspiration for his work at the Jardin des Plantes, like our Kew Gardens, where he said, “it seems to me that I enter into a dream.” But the vegetation in his painting is not accurate and it looks like there is a rubber plant in the foreground on the right and to the left the leaves are rather like those of a snake-plant; both were commonly found in French households in the late nineteenth century.

Rousseau visited the galleries in these gardens which displayed stuffed animals, and he also went to the zoo in Paris. At the height of the colonial period, these places were a form of entertainment were people delighted in seeing exotic and dangerous animals, stuffed or live in cages, from France’s far away territories. He must have made studies or recalled them from memory, but Rousseau’s tiger is a bit odd. It seems to perch, with its haunches high, on foliage that does not yield to its weight; its tail is too long and its red-gummed snarl shows a strange set of teeth that are all the same size and without its menacing canines. It looks frozen, and with the gorgeous variety of greens and highlights of red, set in patterns across the canvas, the painting is far from frightening. Apparently, Rousseau thought his paintings were so alive and intoxicating that he had to throw open the window in order to escape. It’s amazing what a bit of determination and imagination can do to create something magical.