‘A Silence Haunts Me’ by Jake Runestad, as you will read, is an incredibly moving piece of heartbreak, loss, and ultimately resilience. Our own personal struggles in life can sometimes be as severe as Beethoven’s or perhaps less severe. This doesn’t negate our struggle by any means of course, pain, is always relative to every individual. Not only does the collaboration between Runestad and Boss breathe back life into Beethoven’s words, making them relevant 200 years later, they help people who feel unheard, heard.

If you’re a student and do feel like you are struggling with life or school matters, the teachers at FHS are more than ready to support you, and you can talk to any one of us. In particular, Mrs Pittaway, Mr Cawley, or Mrs Dixon are especially trained to help every one of you, so please do not hesitate to ask for help.

The Story

In 2017, Jake Runestad travelled to Leipzig, Germany to be present at the premiere of Into the Light, an extended work for chorus and orchestra commissioned by Valparaiso University to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Luther nailing his Ninety-Seven Theses to a door in Wittenberg, thereby kicking off the Reformation. While traveling after the concert, Runestad found himself in the Haus der Musik Museum in Vienna, where he encountered a facsimile of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament.

It was the first time he had read the famous text, which is almost equal parts medical history (including Beethoven’s first admission to his brothers that he was going deaf), last will and testament, letter of forgiveness, and prayer of hope. Runestad was flabbergasted and found himself thinking about Beethoven, about loss, and about the tragedy of one of the greatest musicians of all time losing his hearing. Beethoven put it this way, “Ah, how could I possibly admit an infirmity in the one sense which ought to be more perfect in me than others, a sense which I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession enjoy or ever have enjoyed.”

While researching Beethoven’s output around the time of the letter, Runestad discovered that Beethoven wrote a ballet, Creatures of Prometheus, just a year before penning his testament. “Beethoven must have put himself into Prometheus’ mindset to embody the story,” Runestad noted. “Just as Prometheus gifted humankind with fire and was punished for eternity, so did Beethoven gift the fire of his music while fighting his deafness, an impending silence. What an absolutely devastating yet inspiring account of the power of the human spirit. In the moment of his loss —when he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament — he had no idea how profound his legacy would be”.

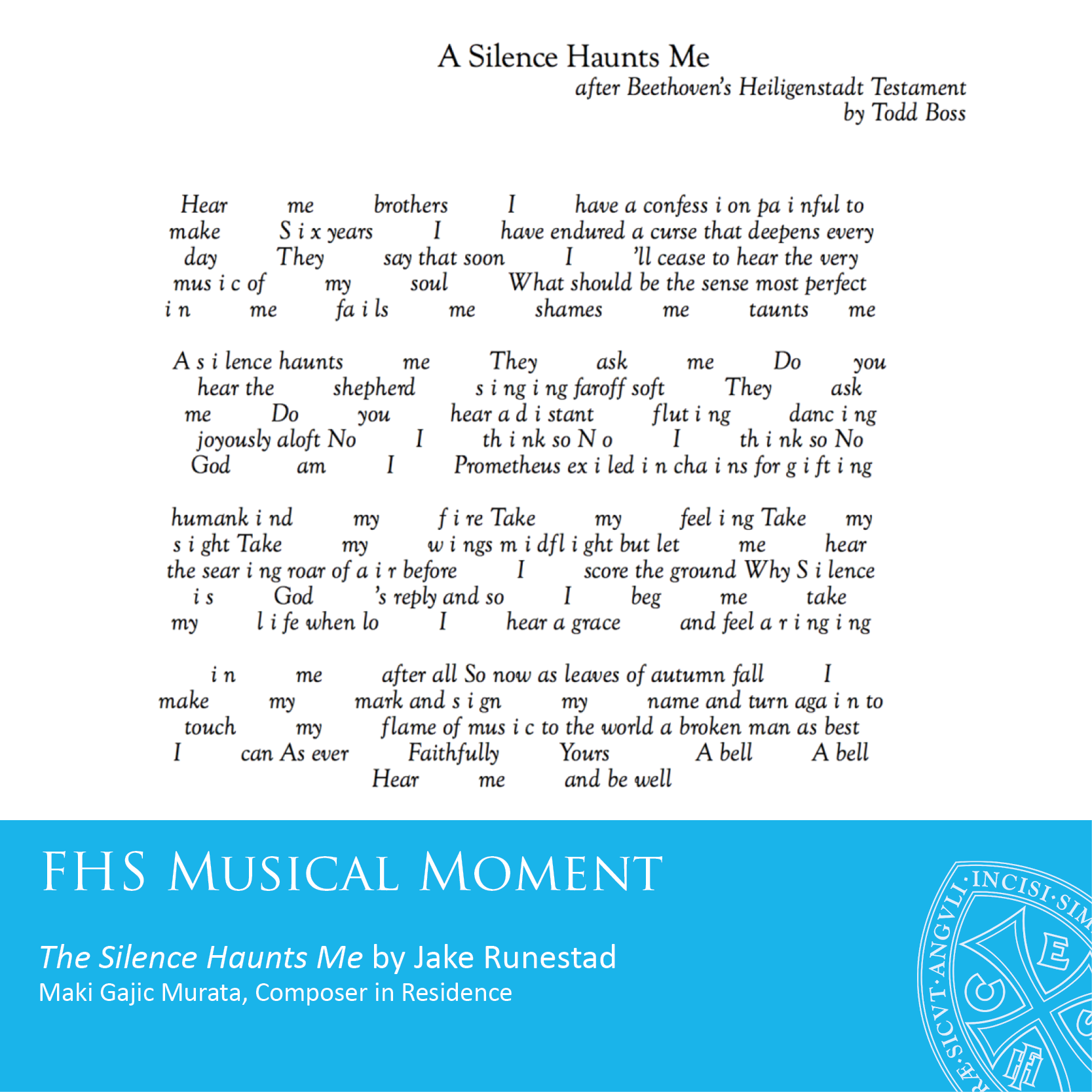

Because of the length of the letter, a verbatim setting was impractical; Runestad turned to his friend and frequent collaborator, Todd Boss, to help. Boss’s poem, entitled A Silence Haunts Me – After Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament creates a scena — a monologue in Beethoven’s voice for choir. The poem is both familiar and intimate; Boss has taken the fundamentals of Beethoven’s letter and spun it into a libretto that places the reader/listener into the same small, rented room as one of the most towering figures of the Romantic Era.

To those words, Runestad has brought his full array of dramatic understanding and compositional skill; A Silence Haunts Me sounds more like a self-contained monologue from an opera than a traditional choral piece. He sets the poetry with an intense, emotional directness and uses some of Beethoven’s own musical ideas to provide context. Stitched into the work are hints at familiar themes from the Moonlight Sonata, the 3rd, 6th, and 9th Symphonies, and Creatures of Prometheus, but they are, in Runestad’s words, “filtered through a hazy, frustrated, and defeated state of being.”

In wrestling with Beethoven, with legacy, and with loss, Runestad has done what he does best—written a score where the poetry creates the form, where the text drives the rhythm, where the melody supports the emotional content, and where the natural sounding vocal lines, arresting harmony, and idiomatic accompaniment — in this case, piano in honour of Beethoven — come together to offer the audience an original, engaging, thoughtful, and passionate work of choral art.

– Program note by Dr. Jonathan Talberg

About the Text

This loose adaptation of Ludwig van Beethoven’s famous Heiligenstadt Testament was unusually difficult to write. Jake suggested the subject matter in a phone call while I was traveling Europe, and it literally haunted me for days afterward, waking me in the middle of the night. I wrote the words “Hear me” and “A silence comes for me” in London between the hours of 2am and 4am. A few days later, I spent the entire 7-hour span of a transatlantic flight writing and rewriting, developing the poem’s unusual shape and format. I finished it several weeks later while in Vienna, and a visit to Heiligenstadt became part of my journey with the piece. I was often in tears during the process. I myself was traveling alone, and so the process was uniquely intense. I was six years into the loss of everything I held most dear, and so I swear I inhabited Beethoven’s state of mind bodily, muscles quaking, unsettled for hours after each of the poem’s twelve major revisions.

I invented many things that don’t appear in Beethoven’s letter. The plea “Take my feeling, take my sight, etc.,” occurred to me as a way of declaiming the terrible irony of Beethoven’s loss, a momentary bargaining as happens as a stage of grief. Comparisons of his plight to that of the accursed Prometheus, Jake’s idea, are in reference to The Creatures of Prometheus, the ballet Beethoven finished a year prior to his sojourn at Heiligenstadt. “A bell” tolls at the end of the letter, and it might be he suddenly hears one, it might be his tinnitus, or it might be a figurative acknowledgement of a newfound hope.

The poem is set in italics to mimic handwriting and arranged against ragged margins to look like a letter. I’ve isolated the letter i wherever it appears, and further isolated nouns that refer to people (I, You, me, brothers, etc.) with nine spaces on either side to isolate them, in recognition of Beethoven’s isolation from himself and others, and in honour of his nine completed symphonies. No punctuation is utilized. All these odd typographical choices force the reader to read the poem with a halting brokenness, just as one might read very old handwriting, but they also attempt to relay the halting and broken frame of mind Beethoven must have been in when he wrote his very sad letter to his brothers.

– Note on the text by poet Todd Boss.

Maki Gajic Murata, Composer in Residence