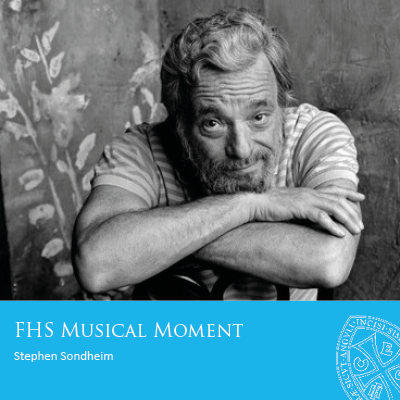

On November 26th, Stephen Sondheim, a titan of the American Musical, died at the age of 91. From the moment in 1957 when he achieved his renown as the lyricist for Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, Sondheim saw himself as an heir to Oscar Hammerstein II, who had written the lyrics for Oklahoma!. Many expected him to revive the flagging American musical by introducing alternative perceptions, relevance and enthusiasm. Sondheim, unlike those before him, did not collaborate with composers or lyricists, but instead wrote both music and lyrics himself.

Sondheim’s music is incredibly recognisable and characterised by the quirkiness of his harmonies, fast syllabic flow of his clever lyrics, and rhythmic invention, whether or not it suited the public’s taste. Sondheim often adopted elaborate dramatic structures and concepts and liked complex storylines laden with significance. Sondheim faced much competition with other competing musicals such as the rising Andrew Lloyd Webber. Sondheim’s Follies, while initially having over 500 performances, receiving seven Tony Awards and numerous revivals, did not recover its investment, whereas Lloyd Webber’s works received much praise and were provocative in the way Sondheim aimed for.

“The point about Andrew,” he said, “is that people just happen to like what he likes… What makes smash-hit musicals are stories that audiences want to hear. And it’s always the same story, how everything turns out terrific in the end and the audience goes out thinking, ‘that’s what life is all about.’ Unfortunately, that’s seldom the kind of material that attracts me.”

Previously, musicals had been a voice of arguably naïve hope. Sondheim’s are about realism and human understanding, thus rebelling against the dream-market ethos of popular theatre.

Send in the Clowns

Arguably one of Sondheim’s most famous numbers. Originally from A Little Night Music, the number has been recorded more than 500 times (notably by Frank Sinatra). A ballad from the second act, the character, Desirée reflects on the ironies and regrets of her life. She looks back on her affair with lawyer Frederik, who was deeply in love with her, but whose proposals she rejected. Meeting him again earlier in the show has finally made her realise that she’s ready to marry him, however, in a ironic twist of fate, he now rejects her and is in an unconsummated marriage with a much younger woman. Reacting to Frederik’s rejection, Desirée sings this song. Sondheim explains:

“Send in the Clowns was never meant to be a soaring ballad; it’s a song of regret. And it’s a song of a lady who is too upset and too angry to speak… she doesn’t want to make a scene in front of Frederik because she recognises that his obsession with his 18-year-old wife is unbreakable. So she gives up; it’s a song of regret and anger, and therefore fits in with short-breathed phrases.”

No one is alone

No one is alone is the finale to Into The Woods, a musical combining the stories of multiple fairy tales. The number is sung by Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, the Baker and Jack during a difficult time. Everyone has had an instance in their life where they feel alone and think they must face their personal battles themselves. Overall, the song is sung to comfort Little Red Riding Hood and Jack as they’ve just lost their mothers and their only family. However, Cinderella and the Baker let them know that they’re not alone and they will support them through their grief. The song serves as a dual purpose as it warns the future generation that you are not alone in the mistakes that you make, and while everyone makes mistakes, these have consequences that affect people outside your personal bubble. The song further explains that “witches can be right/ giants can be good”. Indeed, in the musical, the witch encourages the characters to make good choices, but they ignore her due to the stereotype that witches are evil; and the giant only tries to attack Jack after he kills her husband. Here, Sondheim encourages the listener to rethink certain stigmas they may hold against people within society and take into consideration who they might impact with their actions.

Losing my mind

Losing my mind was originally written for the 1971 musical Follies for the character, Sally Durant Plummer, a former showgirl. The song expresses her preoccupation with Ben, her idealised lover. Sondheim leads Sally from sunrise to sleepless night, revealing that every second of her existence is defined by her longing and explores the extent to which she has lost herself in this make-believe world of undying desire. The paralysis of Sally’s mind is reflected through repeated phrases such as ‘I’m losing my mind’, which is repeated no less than six times.

Being Alive

From the musical, Company, the number, Being Alive, is sung by the protagonist, Robert, at the end of the final act as he realises that being a lone wolf and not maintaining any romantic relationships isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. He declares that he wants to take a chance even if it means getting his heart broken and making sacrifices for the person you love. Being Alive replaced the song Happily Ever After, which was cut from Company for being apparently too dark to serve as a closing number. According to critic, Jeremy McCarter, Sondheim has never been happy with Being Alive, calling it a “cop-out”.

Johanna

The name, Johanna, is the name of three songs in Sondheim’s musical, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. The daughter of Sweeney Todd, who is being held captive by the evil Judge Turpin is sighted by Anthony, a sailor, who hears Johanna singing to the caged birds being sold outside her window and relating to their captivity. Anthony, immediately falling in love, sings about saving her and helping her survive her demons. The song acknowledges the discomfort of love at first sight and saviour complexes. There are some dark undertones in the song as Anthony wishes to “steal” Johanna away even though they haven’t even met yet. The musical has predominant themes of power and control, which is highlighted even in the innocent Anthony as he wishes to possess Johanna, switching her a less cruel owner. As a woman whose autonomy is constantly curbed men, Johanna has no true control over her life until the end of the musical. Sondheim raises these problems to the audience, forcing us to question societal norms when it comes to the treatment of women.

Miss Murata – Composer in Residence